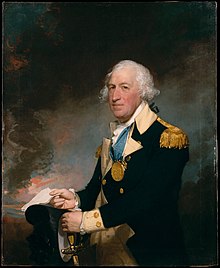

Horatio Gates

Horatio Gates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 26, 1727 Maldon, Essex, Great Britain |

| Died | April 10, 1806 (aged 78) New York City, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1745–1769 1775–1783 |

| Rank | Major (Great Britain) Major general (United States) |

| Commands | Continental Army

|

| Battles / wars | |

| Signature | |

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727 – April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battles of Saratoga (1777) – a matter of contemporary and historical controversy – and was blamed for the defeat at the Battle of Camden in 1780. Gates has been described as "one of the Revolution's most controversial military figures" because of his role in the Conway Cabal, which attempted to discredit and replace General George Washington; the battle at Saratoga; and his actions during and after his defeat at Camden.[1][2]

Born in the town of Maldon in Essex, Gates served in the British Army during the War of the Austrian Succession and the French and Indian War. Frustrated by his inability to advance in the army, Gates sold his commission and established a small plantation in Virginia. On Washington's recommendation, the Continental Congress made Gates the Adjutant General of the Continental Army in 1775. He was assigned command of Fort Ticonderoga in 1776 and command of the Northern Department in 1777. Shortly after Gates took charge of the Northern Department, the Continental Army defeated the British at the crucial Battles of Saratoga. After the battles, some members of Congress considered replacing Washington with Gates, but Washington ultimately retained his position as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army.

Gates took command of the Southern Department in 1780, but was removed from command later that year after the disastrous Battle of Camden. Gates's military reputation was destroyed by the battle and he did not hold another command for the remainder of the war. Gates retired to his Virginia estate after the war, but eventually decided to free his slaves and move to New York. He was elected to a single term in the New York State Legislature and died in 1806.

Early life and education

[edit]Horatio Gates was born on July 26, 1727, in Maldon, in the English county of Essex. His parents (of record) were Robert and Dorothea Gates. Evidence suggests that Dorothea was the granddaughter of John Hubbock Sr. (died 1692) postmaster at Fulham, and the daughter of John Hubbock Jr., listed in 1687 sources as a vintner. She had a prior marriage, to Thomas Reeve, whose family was well situated in the royal Customs service. Dorothea Reeve was housekeeper for the second Duke of Leeds, Peregrine Osborne (died June 25, 1729), which in the social context of England at the time was a patronage plum. Marriage into the Reeve family opened the way for Robert Gates to get into and then up through the Customs service. So too, Dorothea Gates's appointment circa 1729 to housekeeper for the third Duke of Bolton provided Horatio Gates with otherwise off-bounds opportunities for education and social advancement. Through Dorothea Gates's associations and energetic networking, young Horace Walpole was enlisted as Horatio's godfather and namesake.[1]

In 1745, Horatio Gates obtained a military commission with financial help from his parents, and political support from the Duke of Bolton. Gates served with the 20th Foot in Germany during the War of the Austrian Succession. He arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, under Edward Cornwallis and later was promoted to captain in the 45th Foot, under the command of Hugh Warburton, the following year.[3] He participated in several engagements against the Mi'kmaq and Acadians, particularly the Battle at Chignecto. He married the daughter of Erasmus James Philipps, Elizabeth, at St. Paul's Church (Halifax) in 1754. Leaving Nova Scotia, he sold his commission in 1754 and purchased a captaincy in one of the New York Independent Companies. One of his mentors in his early years was Edward Cornwallis, the uncle of Charles Cornwallis, against whom the Americans would later fight. Gates served under Cornwallis when the latter was governor of Nova Scotia, and also developed a friendship with the lieutenant governor, Robert Monckton.[4]

Career

[edit]Seven Years' War

[edit]

During the French and Indian War, Gates served General Edward Braddock in America. In 1755 he accompanied the ill-fated Braddock Expedition in its attempt to control access to the Ohio Valley. This force included other future Revolutionary War leaders such as Thomas Gage, Charles Lee, Daniel Morgan, and George Washington. Gates didn't see significant combat, since he was severely injured early in the action. His experience in the early years of the war was limited to commanding small companies, but he apparently became quite good at military administration. In 1759 he was made brigade major to Brigadier General John Stanwix, a position he continued when General Robert Monckton took over Stanwix's command in 1760.[5] Gates served under Monckton in the capture of Martinique in 1762, although he saw little combat. Monckton bestowed on him the honor of bringing news of the success to England, which brought him a promotion to major. The end of the war also brought an end to Gates' prospects for advancement, as the army was demobilized and he did not have the financial wherewithal to purchase commissions for higher ranks.[5]

In November 1755, Gates married Elizabeth Phillips and had a son, Robert, in 1758. Gates' military career stalled, as advancement in the British army required money or influence. Frustrated by the British class hierarchy, he sold his major's commission in 1769, and came to North America. In 1772 he reestablished contact with George Washington, and purchased a modest plantation in Virginia the following year.

American Revolutionary War

[edit]When the word reached Gates of the outbreak of war in late May 1775, he rushed to Mount Vernon and offered his services to Washington. In June, the Continental Congress began organizing the Continental Army. In accepting command, Washington urged the appointment of Gates as adjutant of the army. On June 17, 1775, Congress commissioned Gates as a brigadier general and adjutant general of the Continental Army. He is considered to be the first Adjutant General of the United States Army.[6]

Gates's previous wartime service in administrative posts was invaluable to the fledgling army, as he, Washington and Charles Lee were the only men with significant experience in the British regular army. As adjutant, Horatio Gates created the army's system of records and orders and helped standardize regiments from the various colonies. During the siege of Boston, he was a voice of caution, speaking in war councils against what he saw as overly risky actions.[7]

Although his administrative skills were valuable, Gates longed for a field command. By June 1776, he had been promoted to major general and given command of the Canadian Department to replace John Sullivan. This unit of the army was then in disorganized retreat from Quebec, following the arrival of British reinforcements at Quebec City. Furthermore, disease, especially smallpox, had taken a significant toll on the ranks, which also suffered from poor morale and dissension over pay and conditions. The retreat from Quebec to Fort Ticonderoga also brought Gates into conflict with the authority of Major General Philip Schuyler, commander of the army's Northern Department, which retained jurisdiction over Ticonderoga. During the summer of 1776, this struggle was resolved, with Schuyler given command of the department as a whole and Gates command of Ticonderoga and the defense of Lake Champlain.[8]

Gates spent the summer of 1776 overseeing the enlargement of the American fleet that would be needed to prevent the British from taking control of Lake Champlain. Much of this work eventually fell to Benedict Arnold, who had been with the army during its retreat and was also an experienced seaman. Gates rewarded Arnold's initiative by giving him command of the fleet when it sailed to meet the British. The American fleet was defeated at the Battle of Valcour Island in October 1776, although the defense of the lake was sufficient to delay a British advance against Ticonderoga until 1777.[9]

Battle at Saratoga

[edit]When it was clear that the British were not going to make an attempt on Ticonderoga in 1776, Gates marched some of the army south to join Washington's army in Pennsylvania, where it had retreated after the fall of New York City. Though his troops were with Washington at the Battle of Trenton, Gates was not. Always an advocate of defensive action, Gates argued that Washington should retreat further rather than attack. When Washington dismissed this advice, Gates claimed illness as an excuse not to join the nighttime attack and instead traveled on to Baltimore, where the Continental Congress was meeting. Gates had always maintained that he, not Washington, should have commanded the Continental Army. This opinion was supported by several wealthy and prominent New England delegates to the Continental Congress. Although Gates actively lobbied Congress for the appointment, Washington's stunning successes at Trenton and Princeton subsequently left no doubt as to who should be commander-in-chief. Gates was then sent back north with orders to assist Schuyler in the Northern Department.

But in 1777, Congress blamed Schuyler and St. Clair for the loss of Fort Ticonderoga, though Gates had exercised a lengthy command in the region. Congress finally gave Gates command of the Northern Department on August 4.

Gates is in the center, with arms outstretched

Gates assumed command of the Northern Department on August 19 and led the army during the defeat of British General Burgoyne's invasion in the Battles of Saratoga. While Gates and his supporters took credit for the victory, military action was directed by a cohort of field commanders led by Benedict Arnold, Enoch Poor, Benjamin Lincoln, and Daniel Morgan. Arnold in particular took the field against Gates' orders and rallied the troops in a furious attack on the British lines, suffering serious injuries to his leg. John Stark's defeat of a sizable British raiding force at the Battle of Bennington–Stark's forces killed or captured over 900 British soldiers–was also a substantial factor in the outcome at Saratoga.

Gates stands front and center in John Trumbull's painting of the Surrender of General Burgoyne at Saratoga,[10][11] which hangs in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. By Congressional resolution, a gold medal was presented to Gates to commemorate his victories over the British in the Battles of Bennington, Fort Stanwix and Saratoga. Gold and bronze replicas of that medal are still awarded by the Adjutant General's Corps Regimental Association in recognition of outstanding service.[12]

Gates followed up the victory at Saratoga with a proposal to invade Quebec, but his suggestion was rejected by Washington.[13]

Conway Cabal

[edit]Gates attempted to maximize his political return on the victory, particularly as George Washington was having no present successes with the main army. In fact, Gates insulted Washington by sending reports directly to Congress instead of to Washington, his commanding officer. At the behest of Gates's friends and the delegates from New England, Congress named Gates to president of the Board of War, a post he filled while retaining his field command—an unprecedented conflict of interest. The post technically made Gates Washington's civilian superior, conflicting with his lower military rank. At this time, some members of Congress briefly considered replacing Washington with Gates as commander-in-chief, supported by military officers also in disagreement with Washington's leadership.

Washington learned of the campaign against him by Gates's adjutant, James Wilkinson. Following a drunken party, Wilkinson repeated the remarks of General Thomas Conway to Gates, which were critical of Washington, to aides of General William Alexander, who passed them on to Washington.[14] Gates (then unaware of Wilkinson's involvement) accused persons unknown of copying his mail and forwarded Conway's letter to the president of Congress, Henry Laurens. Washington's supporters in Congress and the army rallied to his side, ending the "Conway Cabal".[15][16] Gates then apologized to Washington for his role in the affair, resigned from the Board of War, and took an assignment as commander of the Eastern Department in November 1778.

Camden

[edit]In May 1780, news of the fall of Charleston, South Carolina, and the capture of General Benjamin Lincoln's southern army reached Congress.[17] It voted to place Gates in command of the Southern Department.[18] He learned of his new command at his home near Shepherdstown, Virginia (now West Virginia), and headed south to assume command of the remaining Continental forces near the Deep River in North Carolina on July 25, 1780.[19]

Gates led Continental forces and militia south and prepared to face the British forces of Charles Cornwallis, who had advanced to Camden, South Carolina. In the Battle of Camden on August 16, Gates's army was routed, with nearly 1,000 men captured, along with the army's baggage train and artillery. Analysis of the debacle suggests that Gates greatly overestimated the capabilities of his inexperienced militia, an error magnified when he lined those forces against the British right, traditional position of the strongest troops. He also failed to make proper arrangements for an organized retreat. Gates's principal accomplishment in the unsuccessful campaign was to cover 170 miles (270 km) in three days on horseback, heading north in retreat. His disappointment was compounded by news of his son Robert's death in combat in October. Nathanael Greene replaced Gates as commander on December 3, and Gates returned home to Virginia. Gates's devastating defeat at Camden not only ruined his new American army, but it also ruined his military reputation.

Board of inquiry

[edit]Because of the debacle at Camden, Congress passed a resolution calling for a board of inquiry, the prelude to a court-martial, to look into Gates's conduct. Always one to support a court-martial of other officers, particularly those with whom he was in competition for advancement, such as Benedict Arnold, Gates vehemently opposed the inquiry into his own conduct. Although he never was again placed in field command, Gates's New England supporters in Congress came to his aid in 1782, repealing the call for an inquiry. Gates then rejoined Washington's staff at Newburgh, New York. Rumors implicated some of his aides in the Newburgh Conspiracy of 1783. Gates may have agreed to involve himself, though this remains unclear.[20]

Later life and death

[edit]

Gates' wife Elizabeth died in the summer of 1783. He retired in 1784 and again returned to his estate, Traveller's Rest, in Virginia (near present-day Kearneysville, Jefferson County, West Virginia). Gates served as vice president of the Society of the Cincinnati, the organization of former Continental Army officers, and president of its Virginia chapter, and worked to rebuild his life. He proposed marriage to Janet Montgomery, the widow of General Richard Montgomery, but she refused.[21]

In 1786, Gates married Mary Valens, a wealthy Liverpudlian who had come to the colonies in 1773 with her sister and Rev. Bartholomew Booth, who ran a boys' boarding school in Maryland.[22] Booth had been the curate for the "Chapel in the Woods," later to become Saint John's Church at Hagerstown, Maryland. Many have suggested that Gates freed his slaves at the urging of his friend John Adams along with the sale of Traveller's Rest in 1790.[23] This narrative was popularized in 1837 by the Anti-Slavery Record, an abolitionist publication.[24] The paper produced an account of the event in which Gates supposedly “summoned his numerous family and slaves about him, and amidst their tears of affection and gratitude, gave them their freedom.”[24] In fact, the terms of the deed of sale for Traveller's Rest indicate that Gates sold his slaves for £800 together with the plantation.[25] The deed did not immediately free any of Gates's slaves, rather it stipulated that five would be free after five years; the remaining eleven would have to wait until they reached the age of twenty-eight.[25] Nevertheless, even this limited gesture toward emancipation surpassed the other major generals of the revolutionary era; for none but Gates made any efforts to emancipate their slaves during their lifetimes.[25]

The couple thereupon moved to an estate at Rose Hill in present-day midtown Manhattan, where the local authorities received him warmly.[26] His later support for Jefferson's presidential candidacy ended his friendship with Adams. Gates and his wife remained active in New York City society, and he was elected to a single term in the New York State Legislature in 1800.[27] He died in his Rose Hill home on April 10, 1806, and was buried in the Trinity Church graveyard at the foot of Wall Street, though the exact location of his grave is unknown.[28]

Legacy

[edit]- The town of Gates in Monroe County, New York, is named in Gates' honor, as is Horatio Street in Manhattan's Greenwich Village, New York City,[29] Gates Avenue, which runs from Ridgewood, Queens, to around Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn,[30] Gates Avenue in Jersey City, Gates Place in The Bronx, NY[31] and Gates County, North Carolina.

- The Gen. Horatio Gates House was his home during the Second Continental Congress at York, Pennsylvania.[32]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Billias, p. 80

- ^ Tuchman, Barbara W. The First Salute: A View of the American Revolution. New York: Ballantine Books, 1988. p.192

- ^ Selections from the public documents of the province of Nova Scotia p.627

- ^ Billias, p. 81

- ^ a b Billias, p. 82

- ^ Horgan, Lucille E. (2002). Forged in War: The Continental Congress and the Origin of Military Supply and Acquisition Policy. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-313-32161-0.

- ^ Billias 1994, p. 85.

- ^ Billias 1994, p. 63.

- ^ * Miller, Nathan (1974). Sea of Glory: The Continental Navy fights for Independence. New York: David McKay. p. 172. ISBN 0-679-50392-7. OCLC 844299.

- ^ Surrender of General Burgoyne

- ^ "Key to the Surrender of General Burgoyne". Retrieved January 20, 2008.

- ^ Adjutant General's Corps Regimental Association Awards Archived April 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 9, 2009

- ^ Mintz p. 228

- ^ Cox, Howard (2023). American Traitor: General James Wikinson's Betrayal of the Republic and Escape From Justice. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. pp. 43–61. ISBN 9781647123420.

- ^ Some historians doubt the existence of an organized effort of Washington's opponents that might be called a cabal. One of those historians, Christopher Ward, nonetheless wrote: "The actual existence of such a conspiracy is of little importance in comparison with the general belief in its existence, which prevailed among Washington's friends in the army and elsewhere. Lafayette asserted it was a fact." Ward, Christopher. John Richard Alden, ed. The War of the Revolution. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1-61608-080-8. Originally published Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1952. p. 560.

- ^ Historian John Ferling wrote: "In all likelihood the supposed intrigue never amounted to more than a handful of disgruntled individuals who grumbled to one another about Washington's shortcomings. It is almost certain that Conway never belonged to any cabal, although he doubtless said harsh things about Washington." Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-538292-1. (pbk.) Originally published in hard cover in 2007. p. 282.

- ^ Ward, 2011 (1952), p. 715.

- ^ Ward, 2011 (1952), p. 716.

- ^ Ward, 2011 (1952), p. 717.

- ^ Knight, Peter (2003). Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABL-CIO. p. 540. ISBN 978-1-57607-812-9 – via Google Books.

- ^ Royster, Charles (1979). "PROLOGUE The Call to War, 1775–1783". A Revolutionary People at War: The Continental Army and American Character, 1775–1783. University of North Carolina Press. p. 95. ISBN 0-8078-1385-0.

- ^ Whitehead, Maurice. The Academies of the Reverend Bartholomew Booth in Georgian England and Revolutionary America, Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 1996

- ^ Mellen, G. W. F. (1841). An Argument on the Unconstitutionality of Slavery. Saxton & Peirce. pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b "Horatio Gates, Samuel Washington, and America's Original Sin". New-York Historical Society. July 28, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Procknow, Gene (November 7, 2017). "Slavery through the Eyes of Revolutionary Generals". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- ^ (1) "What remains of Manhattan's Rose Hill enclave". Ephemeral New York. September 3, 2018. Archived from the original (blog) on January 23, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2019 – via WordPress.

(2) Brandow, Rev. John H. (1903). "Horatio Gates". Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association. 3: 17–18. JSTOR 42889819. OCLC 862849155. - ^ Billias, pp. 103–104

- ^ Luzader, p. xxiii

- ^ Moscow, Henry (1978). The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins. New York: Hagstrom Company. ISBN 978-0-8232-1275-0.

- ^ Brooklyn Revealed

- ^ McNamara, John (1991). History in Asphalt. Harrison, NY: Harbor Hill Books. p. 109. ISBN 0-941980-15-4.

- ^ "National Historic Landmarks & National Register of Historic Places in Pennsylvania". CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information System. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on July 21, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2011. Note: This includes Pennsylvania Register of Historic Sites and Landmarks (July 1971). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Gen. Horatio Gates House and Golden Plough Tavern" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2011.

Sources

[edit]- Billias, George Athan (1994). George Washington's Generals and Opponents. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306805608.

- Cox, Howard W. (2023). American Traitor: General James Wilkinson's Betrayal of the Republic and Escape From Justice. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 9781647123420.

- Ferling, John. Almost a Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-538292-1. (pbk.) Originally published in hard cover in 2007.

- Luzader, John F (October 6, 2008). Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution. New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-44-9.

- Mintz, Max M (1990). The Generals of Saratoga: John Burgoyne and Horatio Gates. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04778-3.

- Nelson, Paul David. General Horatio Gates: A Biography. Louisiana State Univ Pr; First edition, 1976. ISBN 0807101591.

- Ward, Christopher. John Richard Alden, ed. The War of the Revolution. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2011. ISBN 978-1-61608-080-8. Originally published Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1952.

External links

[edit] Media related to Horatio Gates at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Horatio Gates at Wikimedia Commons- The Horatio Gates papers, 1726-1828 at the New York Historical Society

- Horatio Gates, 1903, Cornell University Press

- 1727 births

- 1806 deaths

- Adjutants general of the United States Army

- American slave owners

- British Army personnel of the War of the Austrian Succession

- British Army personnel of the French and Indian War

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- American people of English descent

- Continental Army generals

- Continental Army officers from Virginia

- Continental Army staff officers

- British emigrants to the Thirteen Colonies

- Lancashire Fusiliers officers

- People from Shepherdstown, West Virginia

- People from Maldon, Essex

- Military personnel from Manhattan

- Members of the New York State Assembly

- Sherwood Foresters officers

- People from colonial New York

- People from Kearneysville, West Virginia

- People of Father Le Loutre's War

- Burials at Trinity Church Cemetery

- Military personnel from Essex

- Continental Army officers from England